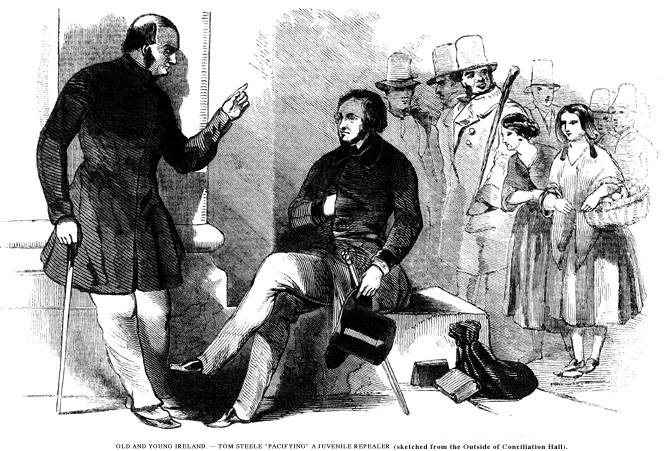

The great split in Conciliation Hall does not appear in any way inclined to close up and heal. Tom Steele may try his persuasive arts, and O'Connell supply any quantity of salve and soothing syrup, but the wound looks angry still. Smith O'Brien now considers himself a real martyr, and his feelings, upon the recent secession of himself and the young Irish party from the great body of repealers, are those of a man suffering from a separation forced upon him by circumstances. He, however, conducts his case quietly, and proves, in the political adversity he is placed, that he has more ability for leadership than some, judging from the obstinate bravado and fiery tone of the cell-imprisoned member of the House of Commons, gave him credit for.

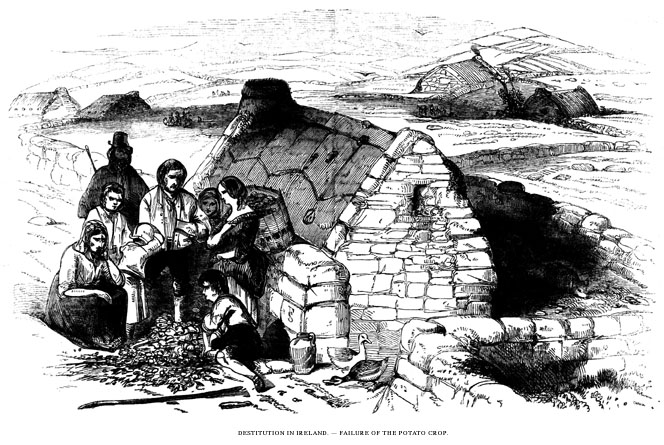

The contrast of moral impatience, as evinced by constant agitation and in the division amongst the repealers on the one hand, and the national submission to the physical evils on the other, has been made the subject of two engravings we present this week to our readers. To us they suggest an apparent inconsistency, that aptly enough illustrates the principles of the young Irish party and the evils they propose to remedy by application to force. Insurrection and rebellion would only lead to an aggravation of misery, the contemplation of which is sufficiently appalling to induce the right minded and humane to shrink from the consequences of recommending, even in the remotest contingency, any appeal to arms, unless, indeed, it were to invite the extirpation of the race as the only remedy against the destitution of which they are the unhappy victims.

But Ireland is not so badly off as all that. England acknowledges the justice of her claims; and often, indeed, had she proved the sincerity of her sympathy. We are also convinced that whilst there are few on this side the channel who do not laugh at the idea of repeal, still all are ready to admit that if we cannot make Ireland prosperous and happy as ourselves, which she ought to be, her inhabitants are justified in endeavouring to do so themselves, even to the severance of all other connection than that which, in the case of the two islands from political motives, might well always impose upon the right of independent self-government. This latter necessity on our part to hold supremacy in Ireland ought to be our excuse, and to the wise and reflective is sufficient reason why the bravest of the Irish people should eschew all idea of resorting to arms, and endeavour to effect the object desired by the force of reason and argument alone.

![]()